Part 2

by Pete Vordenberg, former US Ski Team Head Coach, with additions from Matt Whitcomb, current US Ski Team Head Coach

Continued from Part 1 in the December 2023 issue of the TUNA News

The voyage from dreaming to goal setting requires a little self-knowledge and some courage. To commit to a dream is a courageous act. From goal setting to planning requires knowledge. Like all sciences sports science grows and evolves as more is learned, as new things are tried, incorporated or discarded. That said, this should provide a good foundation to understand some details about preparing for cross country skiing.

Specifics on Preparing for Cross-Country Skiing

The best cross-country skiers are objectively the fittest aerobic athletes in the world. This is measured by V02 max – the ability to utilize oxygen to produce energy. This is because cross country skiing uses the muscles of the entire body all at the same time to ski up and down steep hills on a variable, slick surface, putting a great demand on the heart, lungs and vascular system to supply the muscles with oxygen. Therefore, aerobic training is very important to developing as a cross country skier.

Cross country skiing requires endurance – the ability to work for a long period of time.

Skiing requires power. Power results from applying force (strength), quickly. You must be strong and able to utilize that strength with quickly.

In this way it is not only a highly aerobic sport, it is also a power-endurance sport.

There is also a large technical component to skiing which includes applying an effective, efficient application of power to the skis and poles to propel yourself over the snow at high speeds for long durations. This ability defines good ski technique. One must also develop the agility and skill to navigate difficult terrain, fast down hills, long, steep up-hills in a wide range of snow conditions, from hard ice, to deep, soft powder and everything in between.

Because races are typically between 1km and 50k—or even longer—skiing requires pacing, which demands a close attention and knowledge of yourself. You must also know your equipment, how to use it, pick it, care for it and prepare it for use.

Racing requires all these things plus strategy. Pair this with all the weather winter brings, a true interaction of the body, mind and nature and you have a worthy challenge! Therefore, a strength and resilience of mind, heart and what could be called soul, or your essential self, are perhaps the greatest tools of the skier, and their development is perhaps skiing’s greatest gifts to the skier. It is through preparing for skiing that we develop all aspects of ourselves.

Fundamental Training Theory

- Training Theory is based on super compensation

- Training breaks the body down

- Rest builds the body back up to a level higher than it was previously

Training and rest are balanced so that your body is stressed at a level that is challenging but not harmful and then rested so that it can recover and rebuild from that stress. The body super-compensates to the stress so it is able to handle and, over time, thrive under similar stresses.

Good food, hydration and enough sleep are a vital part of recovery and rest.

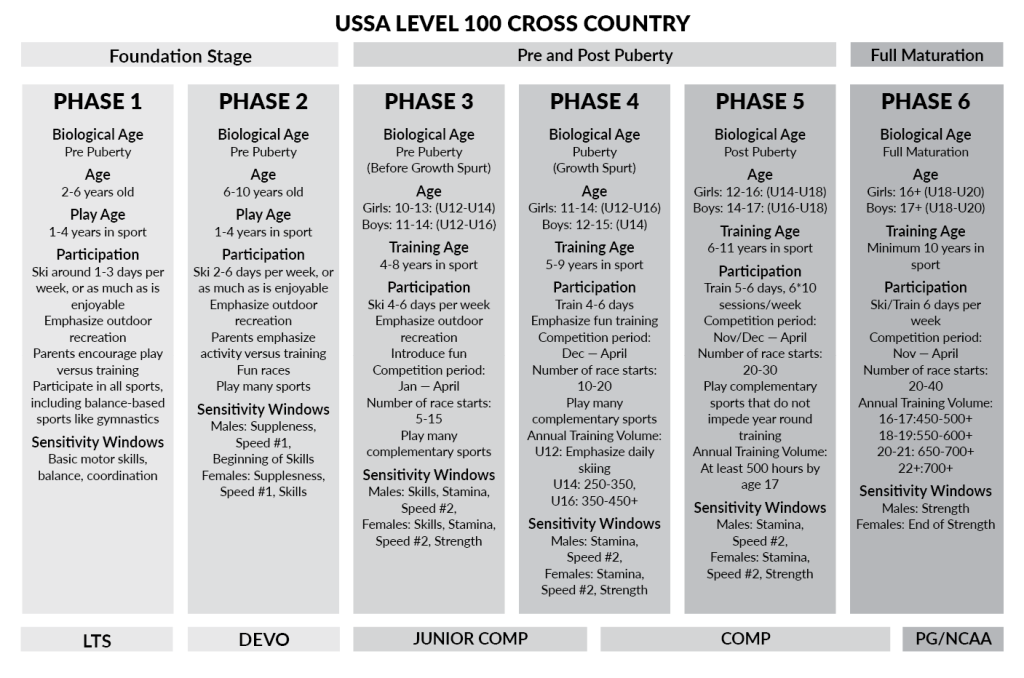

In order for training to lead to continued progress you must continually and gradually change the training load as your body adapts. US Team Head Coach, Matt Whitcomb, stresses that athletes build up gradually in their training over the years. They have noticed younger athletes who do too much too soon and increase their training too much at one time flatten out, plateau and need a big reset over a few years (!) to race fast again and avoid burning out altogether. Most of the US Team — now in or nearing athletic prime — train between 650 and 900 hours a year. The best strategy is to start where you are and gradually, incrementally and patiently build up toward those numbers over many years.

The body makes adaptations to the type of stress it is subjected to. Different types of training elicit different adaptations within the body.

Training is typically defined by training zones or levels. The following describes these levels.

The following portion of this borrows heavily from “Definitions of Training Intensities”, a US Ski Team document created by US Ski Team physiologist Sue Robson and coach Pete Vordenberg.

Level 1 Training

Description

Distance training – this involves medium to long workouts generally at a fairly constant pace. The athletes should get tired from the length of the session, NOT the intensity. If heart rate zones are unknown and lactate checks impractical then breathing is an excellent way to monitor and control the intensity of these sessions. Breathing should be relaxed and rhythmical and it should be very easy to talk.

Main goals

- Increased endurance

- Increased cardiovascular and respiratory efficiency

- Decreased reliance on anaerobic metabolism at low intensity

- Active recovery (when volume is controlled)

- Learn/ingrain proper technique

Physiological changes

- These include long-term structural changes to the heart, lungs and muscle:

- Increased cardiac efficiency, which is caused, by increases in size, elasticity, and contractility of the heart tissue. These changes in heart structure lead to a greater stroke volume and cardiac output resulting in the typical decrease in heart rate both at rest and at any given work load.

- Increased blood volume (mainly plasma tough with some increase in the total red blood cell count)

- Increased capillarization of muscle and lung tissue

- Increased respiratory efficiency (increased tidal volume and oxygen transfer rates)

- Increased oxygen uptake capacity of muscle cells (increased myoglobin content)

- Improved mitochondrial size, number and function (increase in oxidative enzyme concentration)

- Increased muscle fuel storage: glycogen (carbohydrate) & triglycerides (fat)

- Increased efficiency of fat relative to carbohydrate metabolism (glycogen sparing) also resulting in the secondary effect of decreased subcutaneous fat storage if calories are in deficit.

- Long-term neuromuscular adaptations resulting in habitual technique changes. This type of training for distance skiers is done year-round, and makes up about 80% of a skiers total training volume for the year.

Level 2 Training

Description

Distance training – as with level 1, this involves medium to long workouts generally at a fairly constant pace, though some introduction of carefully controlled intervals often in the form of a “fartlek” session are also common. The athletes once more get tired as a function of volume NOT the intensity of the session.

A lactate level of 2 (or the heart rate tested to correspond with this value) is optimal for determining training intensity, however breathing is also a good guide – once more it should be relaxed and rhythmical and easy to talk.

If you have been paying attention to some chatter among endurance nerds of the past few years you have heard about a trend of training more in the 2-3mml zone, something between level 2 and 3. This has been called threshold zone. A lot of training in this zone has been popularized by Norwegian track running stars the Ingebrigtsen brothers. According to Head US Coach, Matt Whitcomb, this is not a trend the coaches of the US Team subscribe to. A 2-3mml pace is quite fast running on the track but remains rather slow skiing on snow for the cost of the higher workload.

The US team and some US racers have experimented with more Level 2 training, but have for the most part returned to being very cautious in their endurance training and do not push the aerobic pace much, trying to stay in Level 1.

We will talk more about Threshold training in the next issue. In a word – be cautious of trends, they come and go. Some athletes thrive almost no matter what and their success can be misleading.

To maximize physiological changes athletes should aim to train predominantly in Level 1 for all distance training. Here within USSA Cross-Country we like to say that “Level 2 happens.” Level 2 “happens” mostly when athletes need to train faster to ingrain proper technique. Elite skiers should be able to train in Level 1 using good technique. Level 2 also “happens” in difficult terrain and during shorter distance sessions, as well as in warm-up and warm-downs for intervals and racing.

Main goals

- As given for Level 1

- As a part of distance sessions where technique is a focus (ski and roller ski sessions)

- As a part of a warm-up and/or warm-down for intervals and races

Physiological Changes

As given for Level 1

Special notes

Pro: Level 2 allows for better biomechanics with a rhythm closer to that used on snow. However due to the increase in intensity great care needs to be taken in the volume selected and its potential to have a greater negative impact on other training sessions due to residual fatigue.

Con: Care needs to be taken with the volume of this type of workout – with the relative intensity being twice that of a level 1 session. It is very easy to overload an athlete with too high a volume of this level of workout. Additionally due to the added intensity these sessions are more likely to cause residual fatigue, which may impact the quality of subsequent training sessions.

Stay tuned for Part 3 – Intensity…