by Jen Santoro

editor Pete Vordenberg

May 1. That’s “Skier’s New Year” around the world. Racing is over, but with that leftover race fitness, most skiers see April as a month of dopamine-inducing adventures. The low-stress, high-satisfaction of crust cruising, backcountry corn-hunting, and maybe low-key loads of laundry are usually off-the-cuff, follow-the-snow pursuits. Then it’s business time again.

Whether you’re a World Cup athlete, Junior Nationals hopeful, or a Boulder Mountain Tour finisher, spring, summer, and fall training is pretty similar. Ski training is unique in that much of it isn’t actual skiing. For those of us who love snow, this can be kind of a bummer, but it’s also great in its diversity, for our minds and our bodies. Repetitive stress on the same muscles and joints that comes from some athletics is not an issue in ski training done correctly. Make no mistake, though, there are some best practices to follow, and that’s where we’re going here.

Before you settle into this article, look back in the previous issues at the series of training articles. In order to keep this one from being a many-part series, the assumption is that you’ve read the others. If not, you can find them at: https://utahnordic.org/training-for-ski-racing/

The Myth of Year-Round Specialization

Those of us who are 70’s and 80’s kids remember a time when kids’ sports were casual, one step up from playing outside with friends. Sports were mostly school or community-based, one at a time, and one didn’t start until the other ended.

Sometime after that, things got pretty serious, and we got to a point where 8-year-olds were playing travel soccer 12 months of the year. It created a large number of premature has-beens and never-gonna-be’s.

The pendulum started to swing, and suddenly the message became loud and clear: “Michael Jordan played three sports in high school and so should you. Nowadays the answer to not specializing in one sport is to see athletes competing in multiple sports during the same season. That’s not what Michael Jordan did.

The thing about ski training is, you can “specialize” in cross-country skiing at any age or stage of development while still competing in other sports. It’s a win-win, with some guardrails.

Ski season is short. The competition season for most skiers is from late November until early March, with a few exceptions. That’s only a little over three months. The biggest chunk of training for that season is finished by December. If success in ski cross-country ski racing is your goal, trying to compete in more than just cross-country skiing in that short season can be counterproductive to your goal.

The rest of the year, in the non-competition season, most skiers are participating or competing in other endurance sports. Most likely those are running and cycling. This is where the myth is busted—one can focus and train year-round for skiing while not always skiing. This is not the same as playing travel baseball for 12 months straight. These other pursuits are excellent for the general fitness and volume requirements for skiing when they are looked at from the viewpoint of year-round ski training.

As for the adults in the room, most master skiers who consider skiing to be their favorite sport are still running, riding bikes, and participating in all sorts of outdoor fun while checking just a few boxes on the ski training list. With just a few tweaks, an endurance athlete can take what they’re already doing and formulate a year-round ski training plan that incorporates all the muscle groups, all the training levels, and most importantly keeps one mentally fresh.

Cross-Country Skiing vs Running and Cycling

At first glance, these fall under the category of “endurance sports.” From a training perspective, they are. There are differences though.

Cross country skiing is a series of bursts of immense power followed by complete relaxation—the better your technique, the more this is true. Pedaling a bike is a consistent effort. The old “90-110 strokes per minute” cadence should be circular in motion, around the entire chainring. If you’re pedal-mashing squares, you may want to invite rollers into your life, but that’s a cycling article. The point is, those bursts of power are more intense on skis than on a bike, even if you’re sprinting or powering over a hard section of singletrack. And cycling isn’t a weight-bearing sport.

Running is closer. It’s weight-bearing, it’s a push from the ground down the track, trail, or road, similar to skiing, but still centered below the waist.

One test compared double poling by skiers and non-skiers. In the non-skiers, double poling was only able to elicit about 60% of their capacity, while skiers were able to access 70 to 80% of their V02 max capacity just double poling. If you’re not training your upper body, you’re leaving a lot of ski speed behind. 1

The reason skiing is as hard and as good as it is, is because it uses the whole body all at once. This is why running or cycling alone isn’t adequate ski training, and that skiing, rollerskiing, and bounding with poles must also be a part of summer ski training. Nothing puts the demand on the cardiovascular system like using the upper and lower body and core all together, all at once.

Strength Training

TUNA’s junior coaching team consults regularly with Art O’Connor. He has brought along some of the best current cycling athletes in the US with his strength programs, which emphasize functional strength, bodyweight, and heavy lifting with good technique. He and his athletes have seen the clear advantages to weight training, with no disadvantages. Skiers do lots of strength training.

General Strength

Specifically, weight lifting. Use proper technique, age-appropriate weights (yes, kids can lift weights safely)2. Work with a trained strength coach (like Art) twice a week and that’s enough to make improvements. Failing that, or access to a gym, a simple pullup bar hanging on door frame can do wonders for your skiing, provided it gets used frequently enough.

Specific Strength

These exercises happen while performing skiing motions such as roller-skiing and snow skiing. They isolate ski-specific muscle groups and move them in ski-related ways.

A summer of general strength and weekly specific strength (like Spenst for the upper body, as well as longer double pole only sessions) will make a skier improve incredibly. Add Spenst and bounding to that, and boom! You’re a skier.

Volume Training

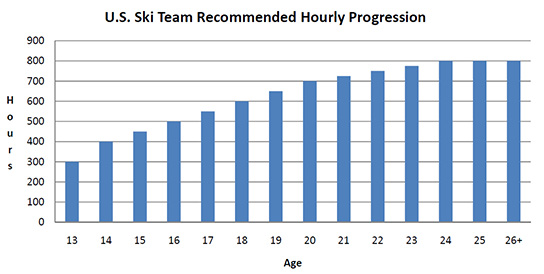

Many athletes are doing their low-level training at too high a heart rate. In the last few issues (and available on the TUNA website at https://utahnordic.org/training-for-ski-racing/), former USSA Cross Country Coach Pete Vordenberg outlined the optimal percentage of low-level volume training as around 80% of the total yearly training hours. 3

The heart rate you’re looking for to complete that training is between 60% and 70% of your max. It feels slow, and you’re only tired from the sheer length of the day. Mistakenly doing these long miles in L2 or higher will cause an athlete to tire out without reaching the number of hours necessary for the low-level training to be effective. Wearing a heart rate monitor (with a chest strap) over time and during competition is an easy way to find that number and stick to it. So is running or riding uphill for a long period of time at an increasing rate until you can’t.

Intensity Training

The US Ski Team coaches have a mantra: “Level 2 (70-80% max heart rate) happens.” It happens when you’re practicing good technique, and in varied terrain. They’ve deemed intentional Level 2 to be less valuable as a training goal. It’s more tiring than Level 1, but less effective than Level 3.

For Level 3 and Level 4, we’re talking intervals. The newest protocols for the top year-round skiers incorporate intensity year-round. That means intervals you’re doing in running or cycling season are going to benefit you for skiing as well, as long as you’re keeping track of the time in each zone and allowing proper recovery from these sessions.

If you’re already doing plenty of non-specific L1 through other sports, adding in two days a week of intense, ski-specific training will accomplish dual goals—you’re getting those ski motions and the intensity training together. You’ll be performing ski-related motions and intensities with your entire body.

For example, one double pole workout with controlled sprints and some L3, and one L3/L4 Spenst and bounding session, even if short, will fill in the blanks missed in other sports.

Competition hours are intensity, and need to be counted as such. Keeping a good training and racing log is a great way to check yourself before you wreck yourself.

Bounding/Spenst/Ski Running/Walking

Ski walking, Spenst, and bounding are probably going to make a bigger difference and require much less equipment than rollerskiing.

Adding poles to a run or hike automatically involves the arms (and core if you make it so) and suddenly your summer workout is benefitting skiing. It’s increasing the capillaries in the parts of your body that don’t normally get repetitive use during a cycling or running session4. Moving your muscles creates more oxygen delivery to those muscles. This is why skiers in that double pole test were able to access more of their maximum performance than non-skiers in this exercise.

Bounding, which is a specific exercise wherein you powerfully stride uphill with poles as if you’re classic striding, emphasizes a specific ski motion. This can be done in short and longer intervals, hitting those Level 3 and Level 4 zones. It won’t hurt your running training one bit, and it will help your skiing. It’s even short enough a workout for cyclists to accomplish without too much of a running base.

Spenst puts a spring in your step. It’s ski-specific plyometrics. That on-off dynamic power used in skiing is trained off skis with Spenst. Even 5 – 10 jumps per leg, per set, is effective.5

Speed

It’s fast, fun, and if you do it right, it doesn’t have to tire you out. You can incorporate speed into long days without it ruining the plan. When short enough (15 to 20 seconds)6 it won’t take much out of you. Runners will do Fartleks, bike racers will sprint for road signs on long rides to break the monotony of 5-hour slogs in the spring. Just don’t sprint for stop signs.

Rollerskiing

There is an old, flawed saying, “Practice makes perfect.” In reality, practice makes permanent, and only perfect practice makes perfect. Rollerskiing is an excellent simulation of skiing when it is done correctly. You can also do more harm than good to your skiing.

You may have heard that classic rollerskiing can create bad habits like “late kick”. In order to make a classic ski work on snow, the ski flexes because the skier shifts their entire weight to that single ski. That complete shift exposes the wax pocket to snow, providing propulsion. A rollerski has a ratchet. You can effectively ratchet yourself up Little Cottonwood with zero weight shift all summer, and none of that will transfer to your skis. Practicing that makes it permanent, and bad habits are hard to break in our ever-shortening winter.

So, what about skate? That’s ok, right? Well….one can move along quite quickly on the bike path by pushing the skate ski hard against the sticky pavement/wheel interface without shifting weight. This is also hard to transfer to snow because snow gives out to varying degrees with that pressure. Skate skis work most effectively with a complete weight shift, just like classic. Again, only perfect practice makes perfect.

If you love to rollerski, or you want to actually improve your snow skiing technique by using rollerskis, here’s how.

- Hire a qualified coach. Rollerski as a means of working on or learning technique correctly, even if you could go faster with poor form.

- If you have ski technique that is well-developed in winter, then rollerski mindfully. Instead of the goal of “4 x 4 minutes of L4,” try the goal of “4 x 4 minutes of perfect technique.” It is almost a guarantee you’ll get the intensity you need.

- Use rollerskiing for your ski specific training and for higher heart rates, and use running, cycling, hiking, etc., for your low, L1 training. That way you’re maximizing your time on rollerskis to be effective for both good technique (that is hard to do in L1) and intensity.

The more experienced you are, and the better your technique, the earlier you can start with rollerski intervals in the season, and the more specific they can be. Even if you’re using rollerskiing just for double poling (a good strategy for runners and cyclists), you’ll want to build up gradually and be sure to use correct poling technique to keep from injuring your elbows.

Periodization

For a World Cup level skier, a training plan is broken into periods for the year. Those might be preparation, pre-competition, and competition, and those could be broken into smaller pieces.

With multiple sports in the mix, periodization of your ski plan is complex, but not impossible. If, for example, you race the ski season from the Thanksgiving to March, take some time off for active rest.

Assuming the spring/summer/fall seasons are similar sports, look over your goals. Pick your big rocks – the focus races. Use the little rocks (minor races) as some of your intensity, and don’t forget to put that in the calculation. Program intervals to support competition. Finally, fill in the blanks with that volume and don’t neglect strength, speed, and ski-specific work.

This is a very simplified overview of something that could be a stand-alone article. Training overloads your body a proper amount to improve, rest allows recovery, and if it’s done correctly each phase is a step up in fitness. You need time to achieve the volume and intensities necessary for the competition you do, while also making sure to give your body the rest it needs to accomplish your goals. Having a good coach to help with planning is invaluable. A good ski coach can write a successful plan with another sport as training, since most cross-country ski coaches have participated in those other sports. Many coaches in other sports don’t know enough about cross-country skiing to do that. Coaching is both an art and a science, and a well-trained and experienced coach is usually behind a successful athlete.

The 10% Rule

There was a saying in cycling, and probably in other sports that went something like, “if you don’t get the 10% rule, it will get you.” Each year when you write your goals and then your periodized training plan you should also pay attention to previous years. In general, an increase in training hours of about 10% is reasonable. More than that and you risk overtraining.

This rule isn’t always hard and fast. From week to week, after injury, previous sports, and training mode all come into play7.

In general, you can reasonably increase your volume most effectively when you vary your modes, adhere to your L1 when you’re supposed to, and listen to your body.

The Ego

The fastest way to break all of the “rules” is when your ego is in charge. Training with groups can be very motivating and having a team has proven effective for the current, most successful US Cross Country team in history. This is because they have the self-control to perform the prescribed workout in their plan in a given session. The same isn’t true for 14-year-olds (or masters). Doing someone else’s intervals is like wearing someone else’s ski boots – it might not fit. Choose your partners wisely.

Being a Skier

If you’re logging miles in many modes, weaving in ski-specific training, general and specific strength, and taking care of yourself with good nutrition and hydration (before, during, and after your workouts), you’re doing most of the job. Throw in some relaxation and visualization—even if it’s not a race, you can visualize your interval session—and now you’re doing what a full-time ski athlete does.

You can consider yourself a skier even when you compete in other sports. The key is always proper planning, goal-setting, and mindfulness. Given the choice between training and resting, resting is almost always the better choice when it comes to mind. And never underestimate the power and knowledge of a qualified coach to help you plan your training to reach your goals.

1. The upper body in skiing. (n.d.). NordicSkiRacer. https://nordicskiracer.com/news.asp?NewsID=1734

2. Strength training: OK for kids? (2023, December 15). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/tween-and-teen-health/in-depth/strength-training/art-20047758#:~:text=Kids%20can%20safely%20lift%20light,Focus%20on%20good%20form.

3. Pete Vordenberg. (2024, March 4). Preparing for cross country skiing – Part 2 – The Utah Nordic Alliance. The Utah Nordic Alliance. https://utahnordic.org/2024/03/04/preparing-for-cross-country-skiing-part-2/

4. M.H. LAUGHLIN and B. ROSEGUINI. (2008, Dec). MECHANISMS FOR EXERCISE TRAINING-INDUCED INCREASES IN SKELETAL MUSCLE BLOOD FLOW CAPACITY: DIFFERENCES WITH INTERVAL SPRINT TRAINING VERSUS AEROBIC ENDURANCE TRAINING. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654584/

5. What is Spenst Training? (n.d.). NordicSkiRacer. https://nordicskiracer.com/news.asp?NewsID=4895

6. Energy systems and training for Cross-Country Ski race courses – FasterSkier.com. (n.d.). https://fasterskier.com/2019/10/energy-systems-and-training-for-cross-country-ski-race-courses/

7. Johansson, R. (2021, December 3). A new approach to the 10 percent rule. TrainingPeaks. https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/a-new-approach-to-the-10-percent-rule/